This post has been contributed by Anthony Fisher, a Lecturer in Philosophy at the University of Washington. Previously, he was a Research Fellow (2016-19) and a Newton International Fellow (2014-15) at the University of Manchester. He works on metaphysics and the history of philosophy. At Manchester, his first project was on the philosophy of Samuel Alexander. In June 2021, he edited a collection of essays that celebrates the centenary of Alexander’s Space, Time, and Deity, published with Palgrave Macmillan.

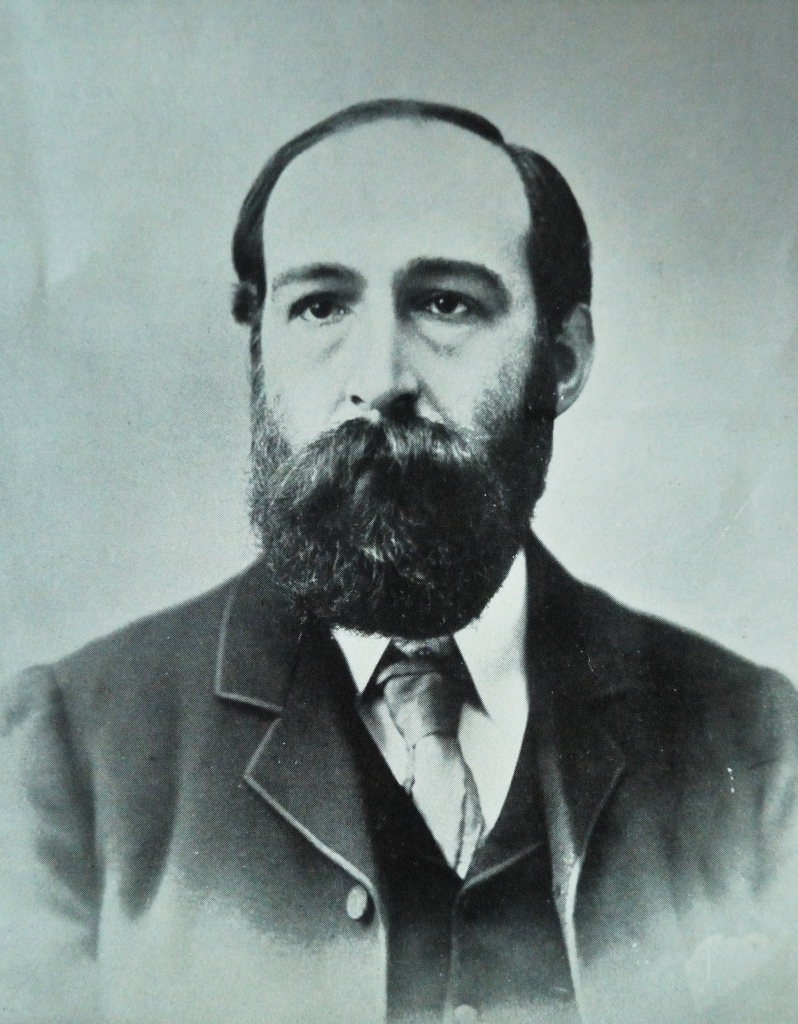

Samuel Alexander (1859-1938) was the first Samuel Hall Professor of Philosophy at the University of Manchester, from 1913-1924. Born in Australia, he made his way to the University of Oxford first as a scholar and then a fellow during a phase in philosophy where British idealism was the dominant trend in reaction to the theory of evolution and its explanatory application beyond biology. He became an influential philosopher, defending a unique metaphysical system in the realist tradition. The Faculty of Arts building at the University of Manchester now bears his name and still contains his bust from 1925.

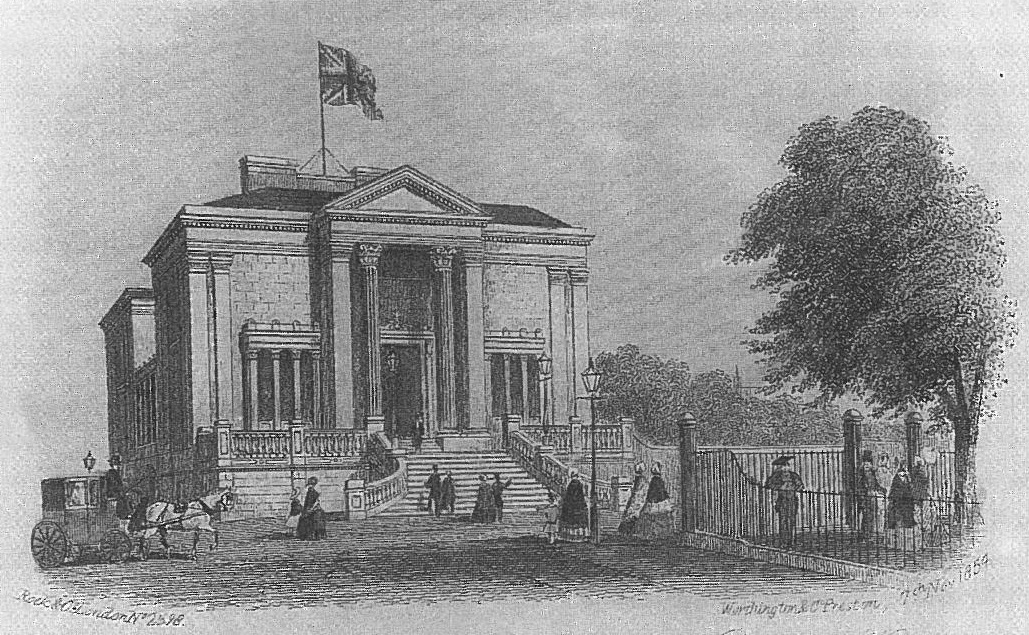

Alexander first arrived in Manchester as Professor of Logic, Mental and Moral Philosophy at Owens College in 1893, when Owens College was a constituent university college of the Victoria University. He was deeply involved in the campaign to make the Manchester constituent its own independent university. He presented his case to The Speaker on 1 March 1902 and again in the Manchester Guardian on 11 June 1902, which was published as a pamphlet titled A Plea for an Independent University in Manchester by Sherratt and Hughes later that month. The timing on his efforts mattered significantly. In June of the previous year, the University Court appointed a committee to investigate the case for dissolution. This committee sent its report, which proposed separation, to the University Court on 31 May 1902. The University Court at the 1902 Convocation on 23 June 1902 voted on whether to support the break-up of the constituent colleges (it did: 137 in favour, 87 not).[1] Owens College received its independence in 1903. For more on the history of the Victoria University, see John Taylor’s ‘1880-2020: A Forgotten Anniversary‘.

For many, Alexander’s pamphlet proved convincing. Owens College was just over 50 years old by 1902. It had had its ups and downs since 1880 within the federal system that was Victoria University. There were many costs and benefits of such an educational system. Liverpool was keen to free itself, whereas Leeds (Yorkshire College) was steadfast in keeping the union alive. Manchester was somewhat on the fence. Alexander’s position on the issue was shared by others such as T.F. Tout, but for him there were philosophical arguments that supported it, arguments that were imbued with his character and that informed his very conception of a university.[2]

In philosophy, Alexander defended realism but also believed in system and often theorised in systematic terms. Everything is somehow related to everything else and so the best comprehensive explanation is couched in terms of a system. In his metaphysics, spacetime is the fundamental matrix of reality, as he elaborates in Space, Time, and Deity.[3] At the social level, society and social institutions are organic social wholes (which emerge from spacetime, although this is irrelevant here). These social wholes undergo evolutionary progression, just like everything else. Such an idea dates back to Hegel, which Alexander recognised in his early work along with the realisation that Darwinian evolution and Hegelianism converge to some extent on this truth.[4]

From this perspective, the social institution – in this case, Owens College – is inexorably caught up in the organic growth of the city (Manchester) in which it is located and the city’s surroundings (now Greater Manchester). The social whole is the larger organism, namely the city, with the institution as one aspect or part of that social whole. The social whole is its own system. Alexander added that the people of Manchester felt this social reality too; there was growing and intense ‘sentiment of organic connection’, he writes.[5] We now have the makings of an argument, which can be formulated as follows.

The university is one integral aspect of a social organic whole, which is the city and its surroundings. If the university is a constituent of some other external system, then it cannot fill its role in its real place in its social whole. In other words, in order to fill its role the university should be independent of some other system that has parts external to the university and its city. Therefore, Owens College should be an independent university. A subsidiary point is that the federal system is not a true system exhibiting a unity that makes that thing unqualifiedly one. Rather, the federal system is an aggregate or sum of social entities. An aggregate or sum – like a sand dune – is a thing that derives its reality from its parts. It is something that is built from the bottom up. Hence it is not the sort of thing that can suitably govern the parts from above.

By freeing Owens College it would be able to continue its natural course of being caught up in the social life and economic growth of Manchester. People of Manchester would care more deeply for their institution if it was truly theirs. University and community are two sides of the same coin. Furthermore, deans, lecturers, staff, and others at the university would be able to let in new disciplines and faculties such as those of medicine and law, which is exactly what the University of Manchester did. Finally, the university would be able to tend to the specific needs of Manchester and its distinctive development and expansion in the Northwest. The vision of a local and regional university did not foster an inward parochialism, as it was feared by some. Instead the city with its university – as a unified social whole – would attract students from all over the world.

In presenting arguments for an independent university in Manchester Alexander never implemented a destructive endeavour. Talk of ‘freeing the university’ from the chains of the federal system and talk of ‘independence’ were often seen in a negative light, as if independence implied that the federal system was being dismantled, as if it is something that must be torn down. On Alexander’s view, society and social wholes (such as cities with their universities) progress along evolutionary tracks. In the nineteenth century, there were colleges, university colleges, and universities. Owens College began, as the name indicates, as a college in 1851, then it became a university college in the Victoria University, and its next evolutionary step was to become a university. So, for Alexander, Victoria University was not dissolving, it was evolving.[6]

It should be highlighted that when Manchester became independent its name was the ‘Victoria University of Manchester’. On paper Victoria University was evolving into the Victoria University of Manchester and in principle Manchester could become associated or conjoined with other colleges in the future. So the birth of what is now the University of Manchester occurred in 1880, not 1903. From Alexander’s perspective, Owens College was ready to evolve into something that would be better for all those involved. This evolutionary progression supports the optimism that is needed by the people of a city-with-university to make their institution a superior thing in the future. Manchester was ready to make a great university in the twentieth century, and so it did.

What becomes of the University of Manchester in this century remains to be seen. But lessons can be learnt from Alexander’s conception of a university. Besides the metaphysical underpinnings, he held a practical and what he called liberal conception of the university. His views on this are found in a piece he wrote for The Political Quarterly titled ‘The Purpose of a University’, which he wrote 30 years after Owens College had evolved into the University of Manchester.

According to Alexander, the university is an association of students and teachers. The purpose of a university is for students and teachers alike to pursue knowledge in preparation for a job or profession after graduation as well as in advancing research. Specialised research serves as one way to prepare for the professions because it is engaged in building knowledge of a discipline that grounds the professions that students are preparing for. Acquiring knowledge is the key here; hence, the teacher (lecturer) is meant to teach the student, and not simply examine the student. One flaw with the federal system was its focus on examinations removed from personal instruction. The latter model fuelled in the student an obsession with grades, transcripts and the certificate handed out upon graduation.

Alexander also thought that the university’s job of pursuing higher branches of knowledge grounds the professions of ordinary life. The job prospects of engineers would have been greatly diminished if universities did not acquire and extend knowledge in the sciences such that engineering as a special science could be created. A university, therefore, is essentially bound up with practical issues in life. It is not an institution that cultivates knowledge for its own sake or maintains this goal as its sole purpose.

However, acquiring and extending knowledge must be pursued in a liberal spirit, Alexander says. The word ‘liberal’ is not restricted to the liberal arts. It should be broadened because, he argues: ‘It sets us free from the routine which besets the practice of any craft, it saves knowledge from being merely an acquisition or merely useful, animates it with reason and gives it life and zest’.[7] It describes a spirit that we live when we study any kind of subject, from physics and philosophy to art history. This spirit is directed towards understanding what we know. It thus applies to all branches of knowledge, not just Literature, English, and Poetry. Alexander concludes:

A University thus trains its members to perform their craft with liberation from the mere doing of it, because it supplies them with the enlightening quest of reason. All our studies therefore are pursued, not without regard to their utility for life, but not for the sake of their utility. What the University seeks to provide is the command of a subject, afterwards to be applied, which will make the application worthy of a free man. Such education may justly be called liberal.[8]

In sum, the liberal spirit and the practical drive of the university are unified in the interlocking context of the city and local region of which the university is an intimate and central component. The spread of universities across the world vindicates Alexander’s case for letting Owens College evolve into the University of Manchester and his liberal conception of a university is an important reminder of the real nature of a university.[9]

[1] Fiddes, Edward. 1937. Chapters in the History of Owens College and Manchester University, 1851-1914. Manchester: Manchester University Press, p. 103.

[2] For an account of Tout’s role, see Jones, H.S. 2019. ‘T.F. Tout and the Idea of the University’ in Thomas Frederick Tout (1855-1929): Refashioning History for the Twentieth Century, ed. C.M. Barron and J.T. Rosenthal. London: University of London Press, pp. 71-85.

[3] Alexander, S. 1920. Space, Time, and Deity: The Gifford Lectures at Glasgow 1916-1918. London: Macmillan.

[4] See Alexander, S. 1889. Moral Order and Progress: An Analysis of Ethical Conceptions. London: Trubner and Co, p. viii.

[5] Alexander, S. 1902. A Plea for an Independent University in Manchester. Manchester: Sherratt and Hughes, p. 5.

[6] A Plea for an Independent University in Manchester, op. cit., p. 8.

[7] Alexander, S. 1931. ‘The Purpose of a University’, The Political Quarterly 2(3): 337-52, p. 343.

[8] ‘The Purpose of a University’, op. cit., p. 344.

[9] Images are courtesy of The University of Manchester.

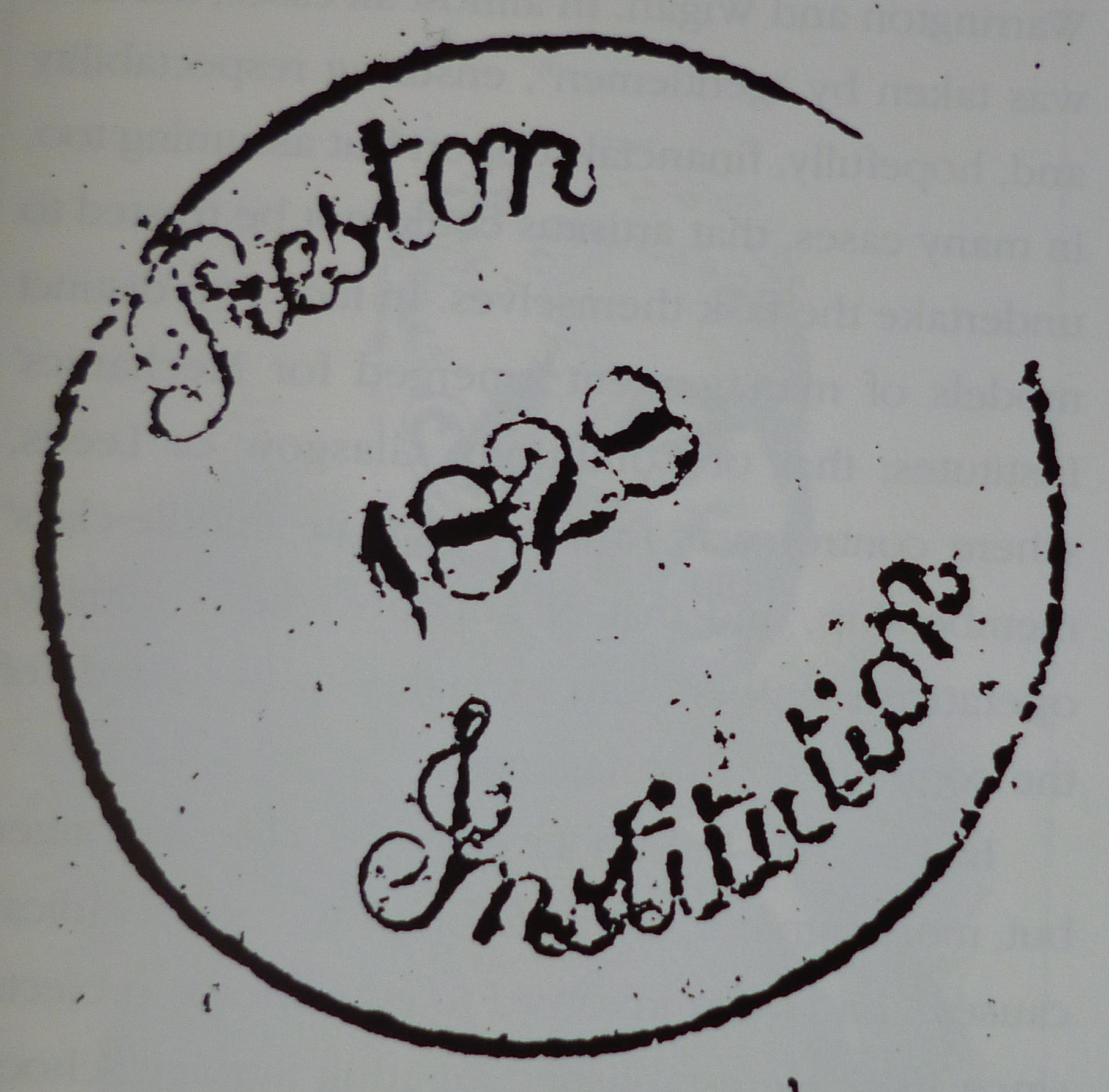

commemorative history. The task is not to write a searching critique, and there is no place for muck-raking, but nor would I wish to be overly critical. In part, that is not the commission but, more than that, UCLan has been my career home for most of my life; I am committed to and have great affection for what it seeks to stand for (even if it often doesn’t succeed), its academic community, and its home city of Preston. Is the entire undertaking, then, illegitimate in that any history written will, by my own admission, be more or less sanitised?

commemorative history. The task is not to write a searching critique, and there is no place for muck-raking, but nor would I wish to be overly critical. In part, that is not the commission but, more than that, UCLan has been my career home for most of my life; I am committed to and have great affection for what it seeks to stand for (even if it often doesn’t succeed), its academic community, and its home city of Preston. Is the entire undertaking, then, illegitimate in that any history written will, by my own admission, be more or less sanitised?